Ever heard the term "current account deficit" and wondered what it means for the average Indian? Think of the current account deficit (CAD) as a country’s financial report card with the world. When a nation is in a deficit, it simply means it's spending more on its international transactions than it's earning.

For a fast-growing, developing economy like India, a certain level of CAD isn't necessarily a good or a bad thing. However, a large or persistent deficit can signal underlying vulnerabilities. This blog will demystify India's CAD, examining its key drivers, its impact on the economy, and the strategies the government is implementing to ensure sustainable growth.

What is the Current Account Deficit?

In the most straightforward terms, a country's current account is a comprehensive record of all its financial transactions with the rest of the world. Think of it as the nation's own "credit card." It measures the total value of all money flowing in from abroad versus all money flowing out.

A Current Account Deficit (CAD) occurs when the total value of money flowing out (from imports, payments, etc.) is greater than the total value of money flowing in (from exports, earnings, etc.). Conversely, a current account surplus means the country is earning more than it's spending internationally.

How is the Current Account Deficit Calculated?

Understanding the formula behind the current account deficit is the key to grasping the numbers in a real-world context. While it may seem complex, the calculation is essentially a sum of all money flowing into the country versus all money flowing out in a given period.

| 💡The core formula for the Current Account (CA) is: CA = (Exports of Goods - Imports of Goods) + (Exports of Services - Imports of Services) + Net Foreign Income + Net Current Transfer |

Where,

- Exports of Goods - Imports of Goods: This is also known as the Balance of Trade. A positive number here means a trade surplus, while a negative number signifies a trade deficit.

- Exports of Services - Imports of Services: This is the Balance of Services. This includes the trade of intangible products.

- Net Foreign Income: This includes investment income, like interest and dividends, that flows in and out of the country.

- Net Current Transfer: This is largely comprised of remittances- money sent home by Indians working abroad.

The current account deficit occurs when the final sum of the formula is a negative number. A surplus occurs when the final sum is positive. In India's context, the CAD is calculated quarterly by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

A CAD is not inherently bad. In fact, fast-growing economies often run deficits because they import capital goods and energy to fuel growth. However, if the deficit becomes too wide, it can put pressure on the rupee, foreign exchange reserves, and inflation, making it more difficult to sustain growth.

Recommended for you

Readers also explored

India’s Unemployment Rate in 2025

Nifty 50 Companies List 2025 : Top 50 Stocks in India

A Historical and Current Perspective: India’s CAD as a Percentage of GDP

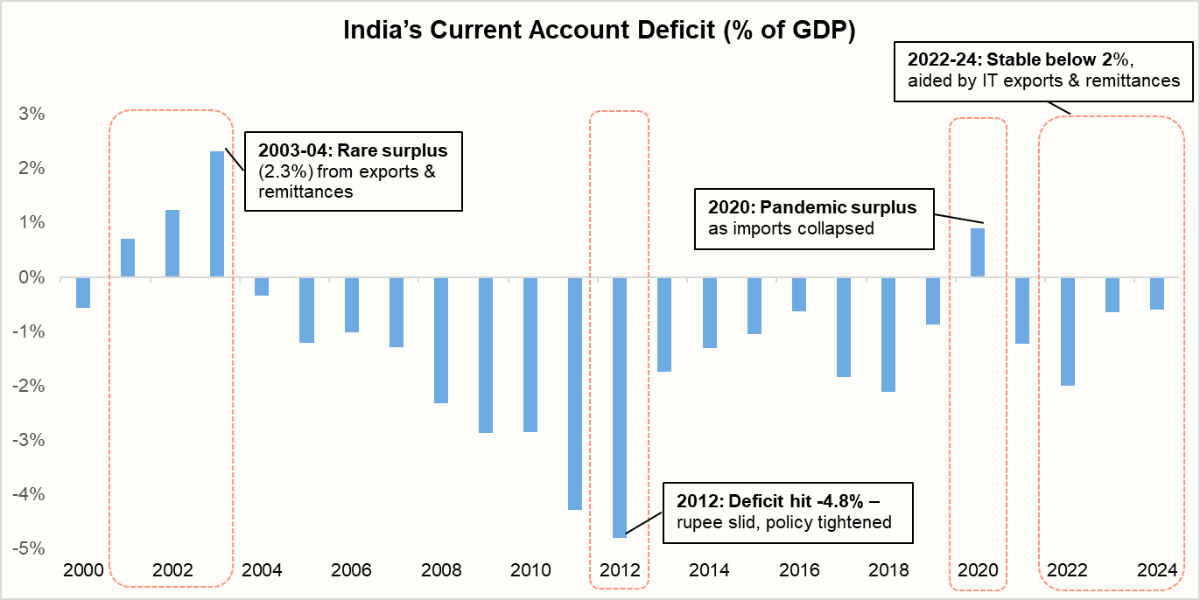

India’s current account deficit (CAD) has moved through sharp highs and lows, reflecting both domestic pressures and global conditions. In the early 2000s, the CAD usually stayed within 1–2% of GDP, a manageable range but indicative of India’s heavy reliance on oil and capital goods imports. The real flashpoint came in 2012–13, when the deficit spiked to 4.8% of GDP, driven by soaring crude prices, weak export performance, and rising gold imports. This imbalance rattled the rupee, spiked inflation and raised fears of a balance of payments crisis.

Since then, India’s external position has become far more resilient. In FY23, the CAD stood at 2% of GDP, but by FY24 it had narrowed to just 0.7%, thanks to easing trade deficits and robust services exports. Remarkably, the March 2025 quarter even posted a surplus of 1.3%, underlining the growing strength of India’s services sector.

The trend has continued into FY26. In Q1 FY26, the CAD came in at just 0.2% of GDP, an improvement from 0.9% a year earlier. Looking ahead, the full-year CAD for FY2025–26 is expected to widen modestly, likely settling between 1.0% and 1.3% of GDP.

Key Drivers of India's Current Account Deficit

India's current account deficit is a critical indicator of its economic health, reflecting the balance of its international transactions. The deficit is primarily driven by a trade imbalance, where the country's imports of goods outweigh its exports. However, other factors also play a significant role. Here are the key drivers of India's CAD:

| Factor | Description | Impact on CAD | Net Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merchandise Trade Deficit | The largest contributor to CAD arises when imports of goods (crude oil, gold, electronics) exceed exports. | High import dependence and weak export competitiveness inflate the trade gap. |  |

| Crude Oil Prices | India imports over 85% of its oil needs. Global oil price swings directly hit the import bill. | Rising oil prices sharply widen the deficit, while stable or falling prices ease it. |  |

| Gold Imports | Strong household demand for gold as a cultural and investment asset. | High-value gold imports add to the deficit without boosting productive capacity. |  |

| Services Trade | Robust IT, business, and telecom service exports generate foreign exchange. | Helps offset part of the merchandise trade deficit, supporting external balance. |  |

| Remittances | Personal transfers from NRIs provide steady foreign currency inflows. | Provides stable forex inflows that consistently ease CAD pressures. |  |

| Exchange Rate | A weaker rupee makes imports costlier but exports more competitive. | In the short run, import costs rise faster than export benefits. |  |

Why India Runs a Persistent Current Account Deficit?

Unlike export powerhouses like China, which run large current account surpluses, India has a persistent current account deficit. This isn't just a short-term phenomenon; it's structural. The primary reason is a fundamental mismatch between what India consumes and what it produces and exports.

- High Import Dependence: Energy (oil, coal, gas), gold, and electronics are core to India’s consumption and industrial needs, but production capacity is limited.

- Weak Merchandise Exports: While services are strong, goods exports face challenges like a lack of scale, limited diversification, and global competition.

- Investment-driven Growth: Fast-growing economies typically import more capital goods, widening the deficit.

- Rising Consumer Aspirations: As incomes rise, imports of luxury goods, automobiles, and electronics also grow.

Unlike export-driven economies such as China, India’s growth model has been more consumption-led, making CAD a recurring feature.

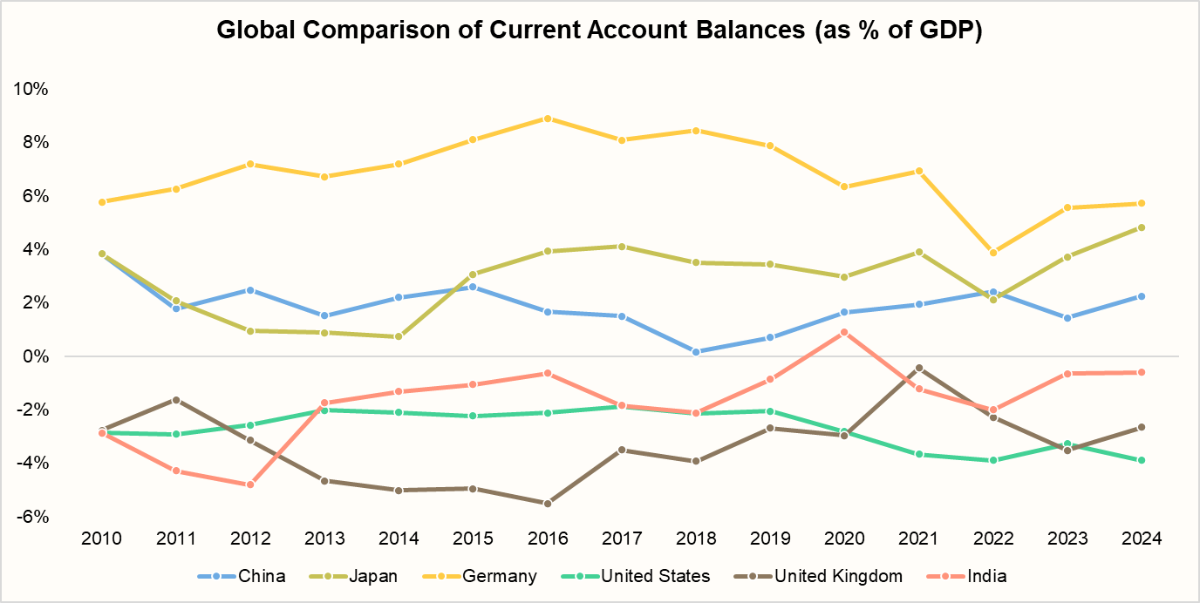

Global Comparison of Current Account Balances

A look at global current account balances shows two very different worlds. On one side are surplus economies like Germany, Japan, and China, where strong exports and high savings keep their balances comfortably positive. Germany often tops the charts with surpluses of 6–8% of GDP, while Japan and China hover around 3% and 2-3% respectively.

On the flip side, deficit economies like the US, UK, and India rely on external capital to fund growth. The US runs a steady 2-3% deficit, cushioned by its dollar dominance. The UK dips deeper, averaging 3-5%.

India, meanwhile, walks a finer line; its deficits of 1–3% are partly cushioned by IT services exports and remittances, and further balanced by consistent capital account surpluses through foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio flows. Together, these inflows ensure the CAD is financed without sharp depletion of forex reserves, though the economy remains vulnerable to oil and gold imports.

This global contrast highlights a simple truth: some nations save and export, while others spend and import.

Is a Current Account Deficit Good or Bad?

A current account deficit often gets painted as a weakness, but the reality is more nuanced. A moderate deficit, say 1-2% of GDP, can signal a healthy, growing economy that is importing capital goods, energy, and technology to fuel expansion. It shows that domestic investment is outpacing domestic savings, a common trait for emerging markets like India.

Problems arise when the deficit widens too much or becomes structurally persistent. A high deficit makes the economy more dependent on volatile foreign capital flows, exposes the currency to pressure, and can trigger balance-of-payments stress.

| Current Account Deficit (% of GDP) | Risk Status | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Below 2.5 | Safe | Stable rupee, easy foreign financing |

| 2.5–3.0 | Borderline | Higher vigilance needed |

| Above 3.0 | Risky | Rupee under pressure, crisis risk |

| Above 4.0 | Crisis Zone | May trigger emergency economic action |

So, a current account deficit isn’t inherently bad. It’s about the size, sustainability, and how it’s financed.However, if the deficit becomes too wide, it can put pressure on the rupee, foreign exchange reserves, and inflation, making it more difficult to sustain growth. A widening CAD often spooks foreign portfolio investors (FPIs), leading to capital outflows. These outflows put further downward pressure on the rupee, raise import costs, and worsen inflation, creating a vicious cycle of depreciation and external vulnerability.

Policy Measures to Manage India’s Current Account Deficit

India manages its Current Account Deficit through a mix of monetary, trade, and structural measures designed to keep the rupee stable and external finances resilient. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) remains central to this strategy, intervening in currency markets when needed and maintaining over $650 billion in forex reserves as a cushion against global volatility.

On the government’s side, policies target both imports and exports:

- Import curbs: Duties or restrictions on non-essential goods like gold and electronics are often introduced during high-deficit periods.

- Export promotion: Incentives and schemes support IT, manufacturing, and high-value sectors, helping improve the trade balance. Alongside, export promotion schemes such as Production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes aim to reduce import dependence.

- Bilateral trade agreements: Diversifying export markets reduces reliance on a few trading partners.

- Remittances: Policies encouraging inflows from non-resident Indians (NRIs) provide a steady stream of foreign exchange.

This layered approach ensures that India can address short-term external shocks while also building structural strength in exports and manufacturing, keeping its CAD at sustainable levels over the long run.

Current Account Deficit and Your Finances

The current account deficit may sound like a purely macroeconomic concept, but it subtly influences personal finances and investment portfolios. A widening deficit usually puts pressure on the rupee, making imports like fuel, electronics, or even foreign education more expensive. For households, this translates into higher inflation and stretched budgets. This hits directly through higher costs of imported essentials like crude oil, which feeds into fuel prices, transportation, and eventually food inflation. Even everyday items, from cooking oil to smartphones, become costlier.

In short, the current account deficit is more than an abstract economic metric; it filters down to how much households spend, save, and earn on their investments. Keeping an eye on it helps both advisors and individuals align portfolios with macro realities.

Conclusion

India’s Current Account Deficit is not just a number on a balance sheet; it reflects how the nation manages its external finances in a volatile global environment.

India’s greatest strength in this regard is its robust and growing services sector and the steady flow of remittances from its diaspora. These act as a powerful cushion against the perennial merchandise trade deficit.

Looking ahead, the long-term solution lies in structural reforms that diversify India’s export base and strengthen its manufacturing sector. By becoming a manufacturing and export powerhouse, India can shift from a chronic deficit to a more balanced or even a surplus position, ensuring greater long-term economic stability and a stronger rupee for all.