GDP-the go-to measure of economic health-relies on a formula we’ve all memorised: C + I + G + NX.

But what if one of those components-government spending (G) - doesn’t belong there?

Recently, US Secretary of Commerce, Howard Lutnick suggested that including government spending in GDP calculations might be a bad idea. Let’s explore why.

The Story

This all started with an X post by Elon Musk: “A more accurate measure of GDP would exclude government spending. Otherwise, you can scale GDP artificially high by spending money on things that don’t make people’s lives better.”

This led to a heated debate among economists, policymakers, and the public! As the controversy gained momentum, Howard Lutnick agreed with the statement during a Fox News Interview.

What is Government Spending?

Government spending refers to money spent by the public sector to serve the public.

The Heart of the Controversy: Inefficient Government Spending

Inefficient government spending is a wasteful expenditure that can distort an economy's true picture, masking inefficiencies and creating a false sense of progress.

Take this striking example:

- Paying 500 workers to dig holes and then fill them back up. On paper, it creates jobs and boosts GDP. But in reality, it produces zero tangible economic or societal value. This is the essence of inefficient spending—an activity that inflates numbers without delivering real benefits.

- Now, contrast that with investing in a high-speed rail network. This kind of spending reduces transportation costs, boosts trade, and generates long-term economic benefits for businesses and citizens. It’s a prime example of efficient government spending—where every dollar spent creates measurable value and drives sustainable growth.

At the core of this heated debate lies a critical question: Should inefficient government spending be included in GDP calculations? The answer could reshape how we measure economic health.

Recommended for you

Readers also explored

Index of Industrial Production: What Is It and How Does It Affect You?

Currency in Circulation: How Much Money Exists in the World?

Beyond the Numbers: The Significance of Government Spending in GDP

Picture this: you’re trying to assess which country has historically performed the best. Most experts rely on a key metric- “Country-level contributions to global GDP”

In a recent LinkedIn Article, Aswath Damodaran explains that China's share of global GDP increased tenfold between 1980 and 2023:

| Percentage Share of World GDP by Geographic Region (1980-2023) | ||||||||||

| 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | |

| U.S. | 25% | 33% | 26% | 25% | 30% | 27% | 23% | 24% | 25% | 26% |

| Europe | 26% | 18% | 26% | 24% | 19% | 22% | 19% | 16% | 16% | 15% |

| Japan | 10% | 11% | 14% | 18% | 15% | 10% | 9% | 6% | 6% | 4% |

| China | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 4% | 5% | 9% | 15% | 17% | 17% |

| India | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Rest of the World | 36% | 33% | 32% | 30% | 31% | 34% | 38% | 37% | 33% | 35% |

Now, consider what would happen if one country decided to remove government spending from its GDP calculation. This move would create a significant issue: it would make comparisons between countries nearly impossible.

More importantly, the inclusion of government spending in GDP calculations (GDP = C + I + G + NX) was formalised by economist Simon Kuznets in the 1930s and has been a globally accepted standard for decades. The methodology has proven useful and robust over many decades, despite evolving economic conditions.

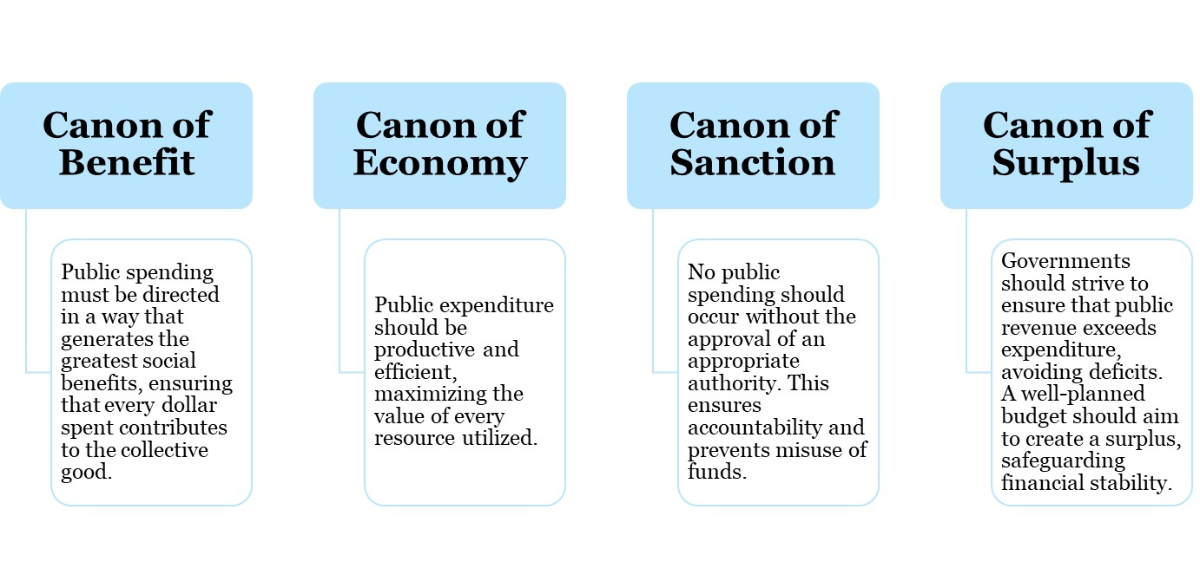

The Four Pillars: Shirras’ Framework for Government Spending

Though government spending is a crucial metric in GDP calculations, Musk’s statement wasn’t entirely inaccurate. It is indeed important that inefficient government spending be minimised or accounted for in a way that enhances transparency and promotes societal well-being.

But what can be done to achieve this? The answer lies in revisiting the four pillars of public expenditure, as outlined by economist George Findlay Shirras:

U.S. Slowdown: Spending Cuts and the Stagflation Fear

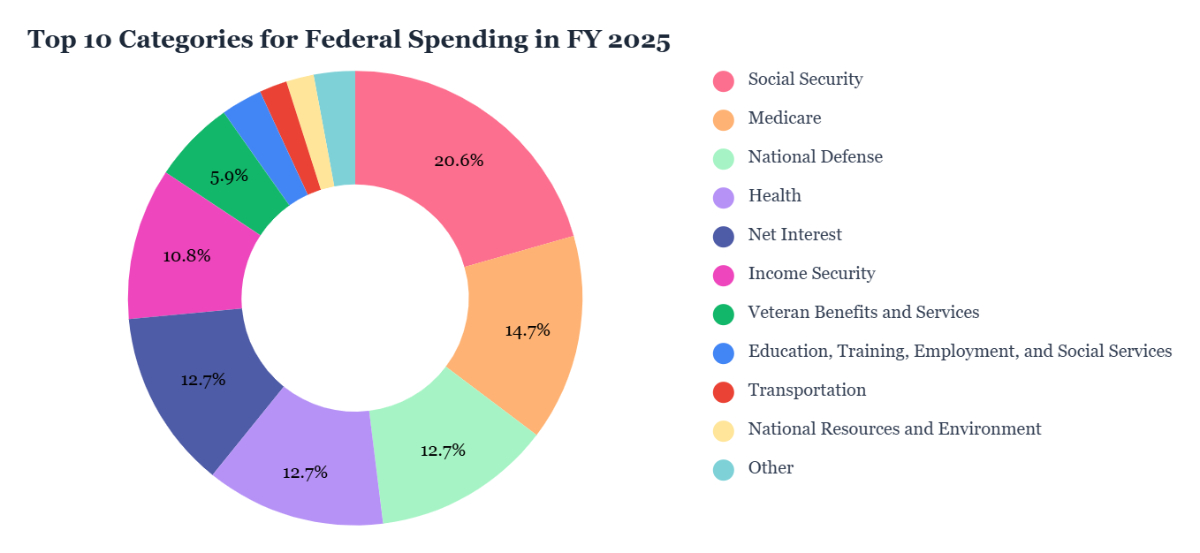

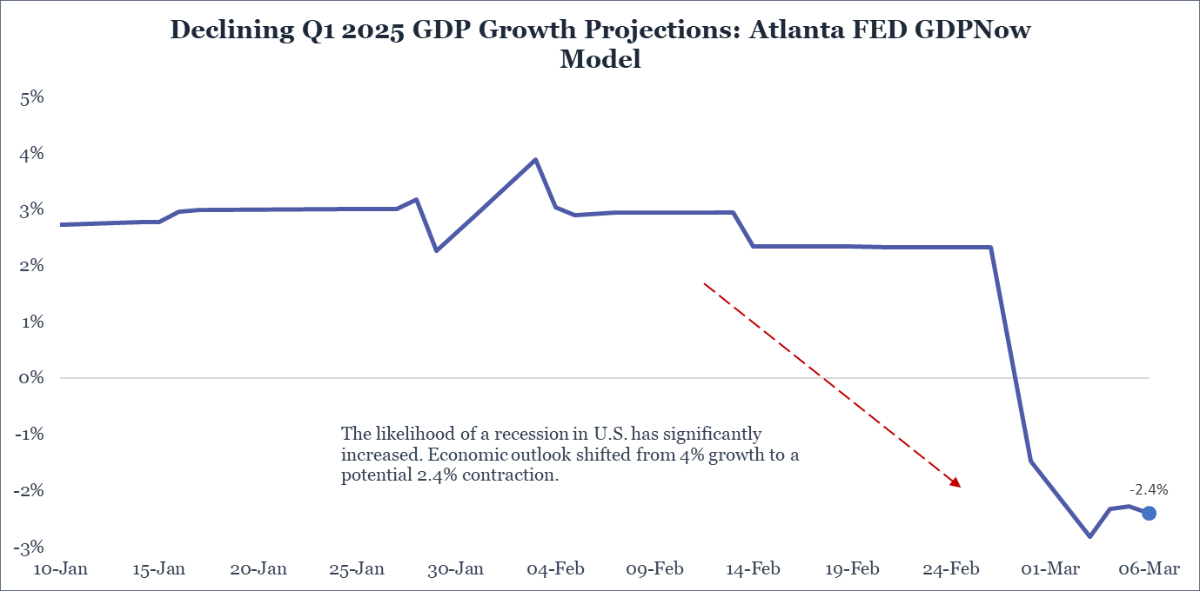

Did you know that the U.S. economic outlook has changed significantly? Fears of stagflation (slow growth and high inflation) are rising. The chart below depicts the Q1 2025 GDP Growth Projections by the Atlanta Fed GDPNow Model.

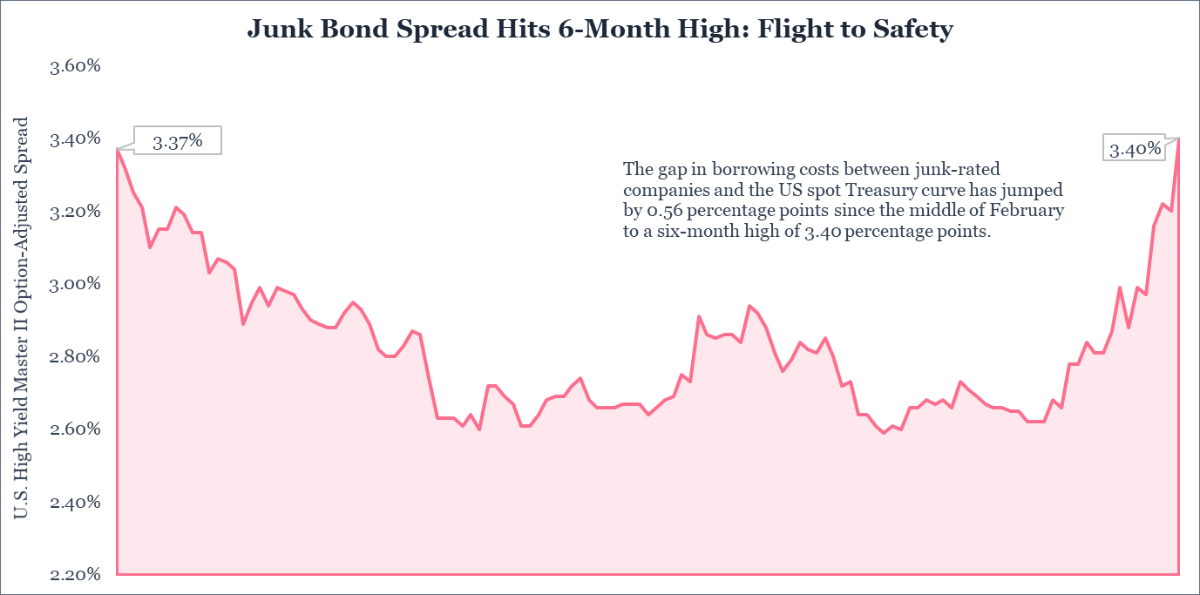

The Fed faces a tough decision:

- If they prioritise fighting inflation by keeping interest rates high, they risk deepening the recession.

- If they prioritise stimulating the economy by cutting interest rates, they risk fueling inflation.

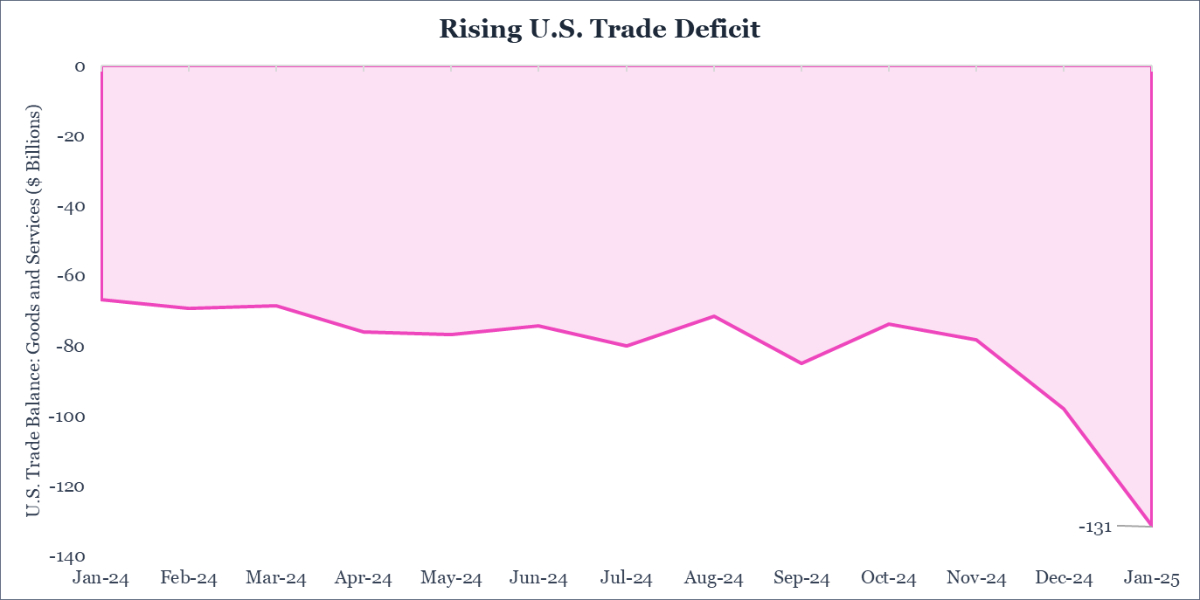

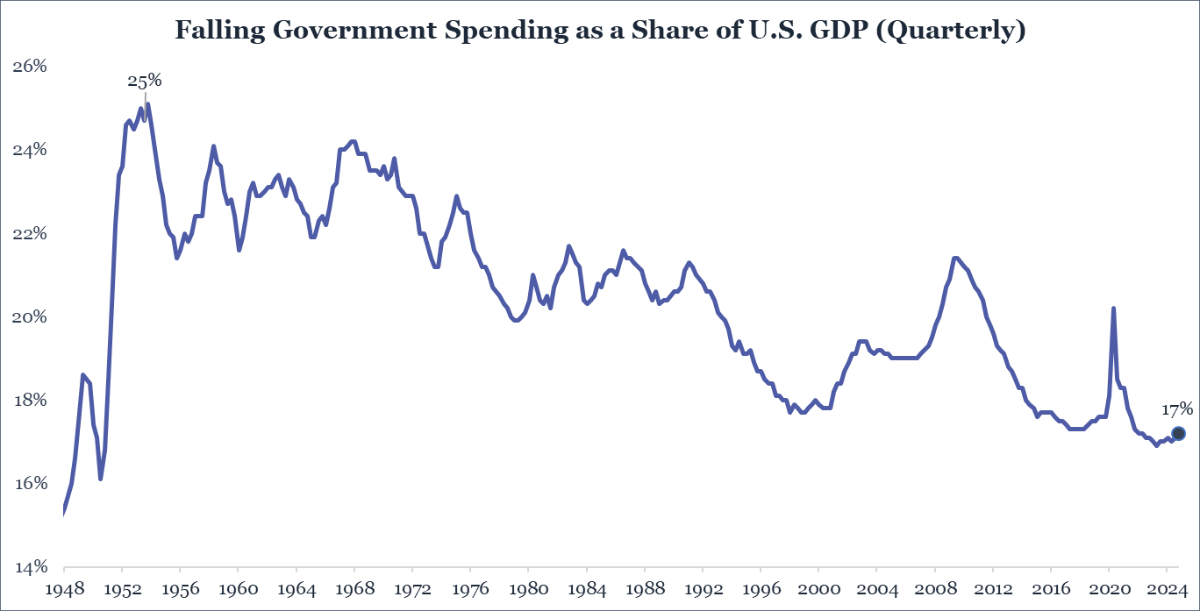

So what is driving such chaos? The major reasons for the U.S. economy's projected slowdown include decreased government spending, slowing consumption and investment, increased imports and public sector job cuts.

Along with this, The Trump administration is intentionally creating economic chaos to restructure the economy. Their goal is to shift from a consumer-driven economy to a business-driven economy. They are using:

- Tariffs to create uncertainty and drive investment into bonds.

- Cuts in government spending to reduce demand.

- Tax cuts and deregulation to boost the supply-side.

- Government spending is a component of GDP. So, when government spending is cut, it directly reduces GDP.

- In a potential stagflation scenario (slow growth and high inflation), the quality of government spending becomes critical. Efficient spending can be a lifeline, while inefficient spending can worsen the situation.

A Look at OECD Spending Review Practices

Countries worldwide are implementing various measures to address inefficient government spending. For example, spending reviews are conducted by many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The OECD is an intergovernmental economic organisation with 38 member countries. These spending reviews help ensure that spending aligns with policy objectives and leads to desired outcomes.

- In 2019 and 2020, Chile initiated a spending review.

- The UK conducts spending reviews every two years. These reviews address its public expenditure to allocate and set out public spending plans for Government departments.

My Opinion

If the Lindy Effect applies, the longer something has existed, the longer it is likely to continue existing into the future. And when it comes to GDP, the future might not be about removing government spending—it might be about redefining how we measure its impact.